John Huston’s Movie Lies A-Moldering on the Screen

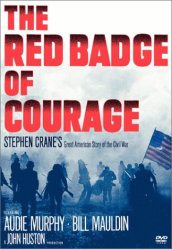

A flop, a bomb, a misfired musket shot upwind on wet powder, John Huston’s 1950 adaptation of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage boils down to about 70 minutes of grizzled extras tramping about the director’s San Fernando Valley ranch. Cannons fire and smoke machines billow. On occasion star Audie Murphy skulks through, dazed and raw-eyed, the contortions of face meant to indicate his character’s current point on an arc stretching from pants-wetting cowardliness to idiot heroism.

A flop, a bomb, a misfired musket shot upwind on wet powder, John Huston’s 1950 adaptation of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage boils down to about 70 minutes of grizzled extras tramping about the director’s San Fernando Valley ranch. Cannons fire and smoke machines billow. On occasion star Audie Murphy skulks through, dazed and raw-eyed, the contortions of face meant to indicate his character’s current point on an arc stretching from pants-wetting cowardliness to idiot heroism.

Murphy, the real-life World War II hero, plays a youth known as The Youth. He speaks a couple times and looks impressively scared and sweaty as narration cribbed from Crane drones on above him. Toward the end, the Youth finds gumption enough to charge from cover directly at the Rebel line.

This is not presented as foolish.

Still, for all its manifold failings, Huston’s Red Badge of Courage stands alongside Rope, Skiddoo or New York, New York as a fascinating failure from a great director. (Some un-fascinating failures from great directors: Jack, Hulk, Hook, The Arrangement, and Huston’s own Annie.)

It’s plotless, naturalistic, stripped of dialogue, and concerned only with the day-to-day grind of soldiering. Instead of the war-movie cliché of a family-like troop of likable fellas defined entirely by their ethnic and regional backgrounds, Huston’s soldiers are a scattered mob: individuals who come together under orders but then break apart under fire.

Crane’s novel details the inner tumult of a loner recruit who cannot connect with the apparently confident men around him. Perhaps attempting to capture this, Huston denies the viewer connection with those men as well. His restless camera seems to happen upon them rather than seek them out. In a number of magnificently framed scenes at a campsite, men argue over battles that might not come, their haggard faces drifting in and out of our view for reasons rare in 1950s Hollywood: these soldiers aren’t there to put on a show the benefit of the audience. Instead, these soldiers simply are. Their lives seem to exist beyond what is shown us.

Huston also denies the audience’s desire to get to know this war. There is no indication of its scale or importance, or of any particular firefight, or of how these men came to give their lives. Instead, Huston gives us squadrons marching. He gives us a river crossing, a charge to a wall, a corpse sprawled on a beaten path, shafts of sun filtered through a tree’s barren limbs. But to Murphy, to himself, and to the suits at MGM, who produced and re-shaped the film, Huston gave something much more interesting: a challenge. How much movie convention could a movie leave out and still be a movie?

The answer can be found in Picture, Lillian Ross’s brisk and illuminating account of all that went awry on The Red Badge of Courage. Turns out, in 1950, even the director behind such gems as The Maltese Falcon, Key Largo, and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre couldn’t get away with so much – or so little. With all the sharp scenecraft Huston refused to bring to his script, Ross reports Louis B. Mayer’s worry that Huston would make a storyless mess as well as producer Gottfried Reinhardt’s related – but more sensitive — warning that the film’s power hinged entirely upon the painstaking presentation of the Youth’s emotional growth.

Unfortunately, Huston failed to capture this. In the finished film, Murphy comes across as a featured player rather than the movie’s pained heart. Huston’s camera checks in with Murphy, affords him some effectively tortured close-ups, and even shows him discussing with a loud soldier the possibility of fleeing once the firing starts. But other than his high emotions there’s nothing distinct or compelling about him.

By not defining his protagonist beyond the rawest of fears, Huston might have been aiming for the universality of human experience. Audiences, though, prefer humans to humanity, so the first test screenings of Huston’s cut of The Red Badge of Courage proved disastrous. Even before the first public screening, Reinhardt and Huston recognized the problem. “A beat is missing,” Reinhardt wrote in a memo reproduced by Ross. “The Youth’s story is somehow lost. The line is broken.”

Houston’s response: “You’re right.”

But Huston had The African Queen to shoot, and he left Reinhardt and MGM to make of The Red Badge of Courage what they could. (His hands-off policy might startle us today, but before the auteur era directors routinely turned their work over to their studio superiors.) Reinhardt took a stab at telling the Youth’s story in a voiceover, but he did so artlessly, and Crane’s prose, out of context, sounds florid and stale.

Ironically, the more of Crane’s words MGM added, the more of his meaning they sliced away. Producers trimmed some violence and a death scene, favored by Huston, that test audiences greeted with laughter. Battles were conflated; the Youth’s eventual charge into combat, which Huston and Crane both considered foolhardy, was re-cut and re-scored until it resembled a conventional moment of war-movie triumph.

Other than Picture, the slapdash result is our only record of the adventures of Huston and his regiments on his ranch in 1950 – and it is fundamentally unsatisfying. For all the scorn MGM has suffered for its hacksawed cut, the evidence seems clear: Huston failed to tell the story of the film’s protagonist and then offered no solution to fix the problem.

His Youth is sweaty blank, from noplace and headed noplace, which might make some thematic sense were it not for the fact Crane himself bothered to invent for him a tender backstory. Scenes from the boy’s pre-war life enliven the novel, including the day the boy felt moved to sign up to fight the South and the wrenching moment he tells his mother he had done so.

Still, the movie has this going for it. The uncertain combination of tough-guy violence, lyric photography, and high-prose narration would later flower in the films of Terence Malick. From Paths of Glory to Platoon to Saving Private Ryan, subsequent war films seem deeply indebted to its grubby, grunts-on-the-move perspective – even as they make greater concessions to convention.

Even after admitting the hole at the center of his movie, it’s doubtful that Huston could have made the concessions that might have muscled The Red Badge of Courage into the great film he and Reinhardt had hoped for. Mayer would have likely turned down a proposal for reshoots. A million and a half dollars had been invested already, and Mayer preferred Andy Hardy and lavish musicals rather than artsy boondoggles. A phrase of Crane’s comes to mind, one found twice in the novel but nowhere in the film: “Firm finance held in check the passions.”